Last summer, I was delighted to be a columnist for #Antibuzz, a radio show about the internet, held by French public radio France Inter. Today, #Antibuzz is back, not as a radio broadcast but as a website, and I’ve been asked to talk once a month about new online storytelling formats. Well, this is great for at least two reasons : those questions are of the highest interest to me, and I already wrote a column last July about Anna Anthropy’s great Rise of the videogame Zinesters, and DIY videogames in general. I therefore decided to write my first digital #Antibuzz piece on another videogames related topic – in my opinion, they are a bottomless source of inspiration for anyone thinking about non-linear narratives and storytelling.

What subject are videogames suited to tackle? They tend to get obsessed by war, they sometimes talk about strange italian plumbers… But are they fit to discuss, criticize, describe, explain or make fun of reality? Apparently not, at least not for Apple. In the past few months/years, the Cupertino brand indeed has banned from the App Store’s virtual shelves several games whose common ground was to hold a point of view on the real world.

But this article’s purpose isn’t to tell you my column’s story – if you’re interested, you can go and browse it – it’s written in French, though. What I’m going to do here is explain how I tried to give it an original form. In fact, this piece itself is a newsgame, or to be more specific, a “Choose Your Own Narrative Chronicle”. I thought this form was particularly suited to the topic of Apple banning newsgames, but I can think of a lot of other journalistic topics that would benefit from such an editorial device.

As I wrote that column, my goal was twofold:

- Introduce the reader to the four cases of Apple censorship that I had listed, while avoiding to write a classic text that would turn into a quite indigestible juxtaposition of examples.

- Try to write a piece of news that is “interactive”, i.e, that is structured around a discussion rather than a discourse.

I am indeed convinced that the second point sums up the internet’s true comparative advantage. For the first time in the history of the press, journalists are truly able to leave a little room to their readers. We can adapt the way we tell them news stories, taking their interests, their questions and their priorities into consideration. This track deserves to be explored. Of course, such news pieces are more demanding for the readers, since it requires them to be active, rather than to “passively” read/watch/listen to a classic, linear journalistic discourse. But it also is potentially more immersive, more intense, more attention-grabbing. Compare this to an university course: which is the one you’d enjoy the most, the one in which you’ll have to participate or the boring, endless lecture?

Then again, I must admit my column’s only partially interactive: the reader has to make choices for the narrative to unfold, but she’s only as “free” as I decided she’d. We are somehow closer to a Socratic approach than to a genuine discussion here. But take it as a first draft, produced in a bare two working days – I felt I had to put myself in real newsroom time constraints for the experiment to be interesting.

Let’s write a system!

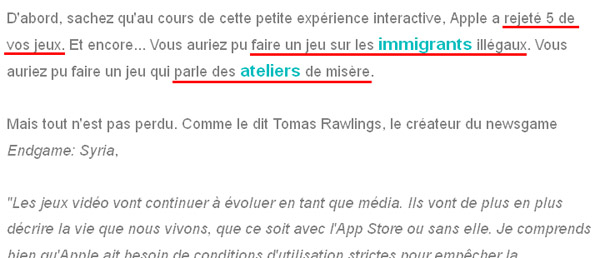

My (hyper)text’s general idea was to provide an overview of the games rejected by Apple because they talk about reality, and the specific reasons why they were turned down. So I started by making a list, noting each game’s specifics. One of them adopted a journalistic approach to deal with the conflict in Syria. Two others had political significance: the first dealt with sweatshops, the second with undocumented immigrants. And the last one, produced by a group of activists, had a “meta” dimension, since by criticizing the smartphones’ production line, it directly challenged Apple.

Besides, I have discarder other games because they did not meet my journalistic angle. For example, Pipe Trouble is an online game that has suffered censorship because it dealt with the conflict between pipelines builders and environmentalists in Canada – it could have been an interesting case. But it is TVO, the Ontarian TV channel, which decided to take the game offline after several complaints, not Apple. Pipe Trouble thereby did not belong to my column.

So far, I had done basic journalistic job: identify the elements of the story, put each into context, and think about how they organize in relation to each other. But it is the rendering of this work that is different. Had I written a classic article, I would have decided to present my information in a static order (What exemple will I use as my piece’s hook? Which one will come next?…). But writing a non-linear chronicle implies to transfer this responsibility to the reader.

I just did a bit of storytelling and asked the user to imagine she’s in charge of a video games compagny. What type of game will she produce? Will she wants to make a political game or a news-related game? Then if she opts for a political game, she’ll have to pick a theme: sweatshops or undocumented immigrants?…

I then tell my reader about real-world game studios that have taken the same decisions she has, and introduce her with the obstacles they faced. Later in the story, when at least one of my reader’s games has been rejected by Apple, I’ll give her the opportunity to “take revenge” and develop another title, this time directly aimed at criticizing the Cupertino firm…

What I’m doing here is I’m giving the reader the opportunity to explore the system I identified through my work as a journalist, and “rebuilt” as an interactive chronicle. In this system, there’s no way Apple would validate a game that talks about a real-world issues. Here’s the conclusion I want to bring my readers to, so that they’d finally ask themselves a question: why such a policy?

To get there, I’m using a game mechanic coined by Ian Bogost: the rhetoric of failure. In my story (as in reality), the reader’s games will always be rejected from the App Store, regardless of the choices she makes – that is, unless she decides to produce a purely distracting title, but in this case she’ll have relinquished her will to use games as a media to describe the real world. Once she’s suffered several rejections, I finally allow the reader to reach the piece’s “conclusion”: an attempted analysis of Apple’s policy, and an inventory of alternative solutions available to developers who’d like their products to exist out of the App Store and its censorship.

Hack your word processor

Here’s for the approach to non-linear journalism. Now how did I manage to build this piece? Well I used a simple program, originally designed to write interactive fiction/CYOA games: Twine. This program has several advantages:

- It’s free

- It is easy

- It allows you to export your text in HTML format, thus making it compatible with every computer, tablet and even smartphone on the market

- It can handle variables, which, through not mandatory, is extremely useful to provide narrative coherence (more on that later on)

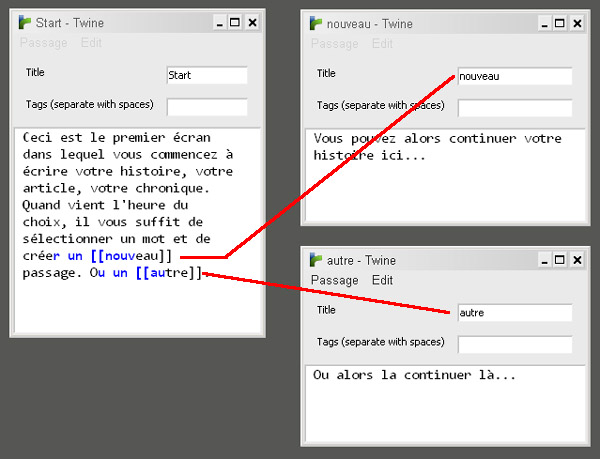

Twine’s interface’s quite austere, but it is very easy to use. You’ll start writing your text in a window, and when you’ll reach the part where you’d like to offer your reader a choice, you’ll simply select a word or phrase and click “create link” in the program menu. This will open a new window, where you’ll continue writing your text. Then, when you’ll export and publish your story, the user will simply have to click the words you selected (which appear in blue and bold) to continue reading.

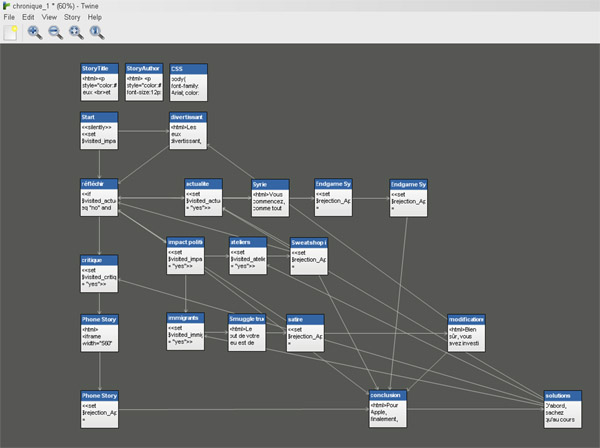

As you write, Twine drawe a map of your story. It’s very handy to check your reader’s available paths through it, and also to make sure they won’t be stuck in any narrative cul-de-sac. In the end, a story diagram may seem complex, but since you write it over the pen, you’ll easily be able to browse through it. For instance, here is how my #Antibuzz column looked like:

Twine also accepts HTML tags, and other media integration: audio, video (Youtube embed works great), images… In a nutshell, through a bit of coding, you’ll be able to do all the things you can do in a basic news website’s CMS. For instance, my chronicle is enhanced with a series of links pointing to many articles written on each case of Apple censorship.

But what makes Twine a far better tool than a classic HTML editor is its ability to handle variables. Through some (once again very straigt-forward) code, you’ll be able to keep track of the passages your reader has reached. This is important because it gives you editorial control over your narrative. If you think the reader should not be able to access a part of your story without having previously read another, just tell Twine to display a link only if another one has already been clicked on. I did that in my column: I only presented the Molleindustria (the studio that produced a game directly critiquing Apple) case after at least one of my reader’s other games has been rejected by the Cupertino company.

Let’s also note that using variable means you actually transform a text into a “real” game. To me, the definition of a game is quite wide: it’s an experience framed by rules and whose result varies depending on user actions. Using a variable to keep track of how many times each player is rejected by Apple before arriving at the narrative’s unfolding, I built one of the very first news-piece-with-a-score!

Would you like to use Twine to conduct experiments in non-linear storytelling (be it journalistic or not), a very simple tutorial is available here. Incidentally, this software can also be very useful to imagine interactive documentaries architectures.

This article’s final point is that I think online newsrooms should learn how to use such tools, the same way they learned how to use Storify, Thinglink, Zeega or other multimedia storytelling tool. This could be an easy, efficient and quick solution to offer their readers new, more interactive, more immersive, and more “loyalty-building” stories. At a time of churnalism and info-zapping, when both readers and journalists are unsatisfied, this could be an interesting path to follow…